https://www.commonsense.news/p/yeste...SigningIn=true

Yesterday I Was Levi’s Brand President. I Quit So I Could Be Free.

I turned down $1 million severance in exchange for my voice.

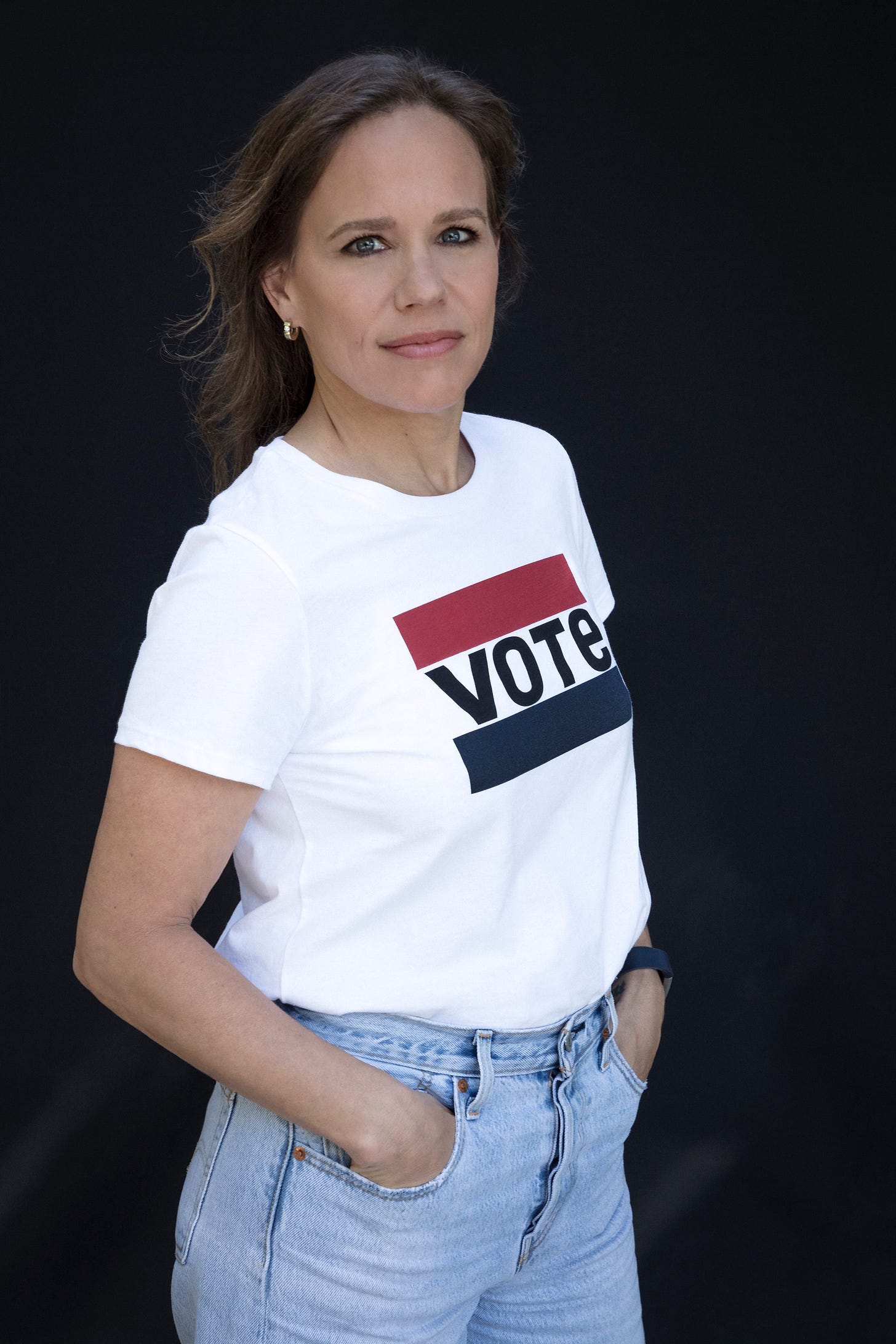

Jennifer Sey

Feb 14

Courtesy of the author.

When I traveled to Moscow in 1986, I brought 10 pairs of Levi’s 501s in my bag. I was a 17-year-old gymnast,

the reigning national champion, and I was going to the Soviet Union to compete in the Goodwill Games, a rogue Olympics-level competition orchestrated by CNN founder Ted Turner while the Soviet Union and the United States were boycotting each other.

The jeans were for bartering lycra: the Russians’ leotards represented tautness, prestige, discipline. But they clamored for my denim and all that it represented: American ruggedness, freedom, individualism.

I loved wearing Levi’s; I’d worn them as long as I could remember. But if you had told me back then that I’d one day become the president of the brand, I would’ve never believed you. If you told me that after achieving all that, after spending almost my entire career at one company, that I would resign from it, I’d think you were really crazy.

Today, I’m doing just that. Why? Because, after all these years, the company I love has lost sight of the values that made people everywhere—including those gymnasts in the former Soviet Union—want to wear Levi’s.

https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:g ood,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com% 2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1e99ee23-8983-4d2a-ad81-414a083baa17

Jennifer Sey (center) in Moscow at the Goodwill Games.

My tenure at Levi’s began as an assistant marketing manager in 1999, a few months after my thirtieth birthday. As the years passed, I saw the company through every trend. I was the marketing director for the U.S. by the time skinny jeans had become the rage. I was the chief marketing officer when high-waists came into vogue. I eventually became the global brand president in 2020—the first woman to hold this post. (And somehow low-rise is back.)

Over my two decades at Levi’s, I got married. I had two kids. I got divorced. I had two more kids. I got married again. The company has been the most consistent thing in my life. And, until recently, I have always felt encouraged to bring my full self to work—including my political advocacy.

That advocacy has always focused on kids.

In 2008, when I was a vice president of marketing, I published

a memoir about my time as an elite gymnast that focused on the dark side of the sport, specifically the degradation of children. The gymnastics community threatened me with legal action and violence. Former competitors, teammates, and coaches dismissed my story as that of a bitter loser just trying to make a buck. They called me a grifter and a liar. But Levi’s stood by me. More than that: they embraced me as a hero.

Things changed when Covid hit. Early on in the pandemic, I publicly questioned whether schools had to be shut down. This didn’t seem at all controversial to me. I felt—and still do—that the draconian policies would cause the most harm to those least at risk, and the burden would fall heaviest on disadvantaged kids in public schools, who need the safety and routine of school the most.

I wrote

op-eds, appeared on

local news shows, attended meetings with the mayor’s office,

organized rallies and pleaded on social media to get the schools open. I was condemned for speaking out. This time, I was called a racist—a strange accusation given that I have two black sons—a eugenicist, and a QAnon conspiracy theorist.

In the summer of 2020, I finally got the call. “You know when you speak, you speak on behalf of the company,” our head of corporate communications told me, urging me to pipe down. I responded: “My title is not in my Twitter bio. I’m speaking as a public school mom of four kids.”

But the calls kept coming. From legal. From HR. From a board member. And finally, from my boss, the CEO of the company. I explained why I felt so strongly about the issue, citing data on the safety of schools and the harms caused by virtual learning. While they didn’t try to muzzle me outright, I was told repeatedly to “think about what I was saying.”

Meantime, colleagues posted nonstop about the need to oust Trump in the November election. I also shared my support for Elizabeth Warren in the Democratic primary and my great sadness about the racially instigated murders of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd. No one at the company objected to any of that.

Then, in October 2020, when it was clear public schools were not going to open that fall, I proposed to the company leadership that we weigh in on the topic of school closures in our city, San Francisco. We often take a stand on political issues that impact our employees; we’ve spoken out on gay rights, voting rights, gun safety, and more.

The response this time was different. “We don’t weigh in on hyper-local issues like this,” I was told. “There’s also a lot of potential negatives if we speak up strongly, starting with the numerous execs who have kids in private schools in the city.”

I refused to stop talking. I kept calling out hypocritical and unproven policies, I met with the mayor’s office, and eventually uprooted my entire life in California—I’d lived there for over 30 years—and

moved my family to Denver so that my kindergartner could finally experience real school. We were able to secure a spot for him in a dual-language immersion Spanish-English public school like the one he was supposed to be attending in San Francisco.

National media picked up on our

story, and I was asked to go on Laura Ingraham’s show on Fox News. That appearance was the last straw. The comments from Levi’s employees picked up—about me being anti-science; about me being anti-fat (I’d retweeted a study showing a correlation between obesity and poor health outcomes); about me being anti-trans (I’d tweeted that we shouldn’t ditch Mother’s Day for Birthing People’s Day because it left out adoptive and step moms); and about me being racist, because San Francisco’s public school system was filled with black and brown kids, and, apparently, I didn’t care if they died. They also castigated me for my husband’s Covid views—as if I, as his wife, were responsible for the things he said on social media.

All this drama took place at our regular town halls—a companywide meeting I had looked forward to but now dreaded.

Meantime, the Head of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at the company asked that I do an “apology tour.” I was told that the main complaint against me was that “I was not a friend of the Black community at Levi’s.” I was told to say that “I am an imperfect ally.” (I refused.)

The fact that I had been asked, back in 2017, to be the executive sponsor of the Black Employee Resource Group by two black employees did not matter. The fact that I’ve fought for kids for years didn’t matter. That I was just citing facts didn’t matter. The head of HR told me personally that even though I was right about the schools, that it was classist and racist that public schools stayed shut while private schools were open, and that I was probably right about everything else, I still shouldn’t say so. I kept thinking:

Why shouldn’t I?

In the fall of 2021, during a dinner with the CEO, I was told that I was on track to become the next CEO of Levi’s—the stock price had doubled under my leadership, and revenue had returned to pre-pandemic levels. The only thing standing in my way, he said, was me. All I had to do was stop talking about the school thing.

https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/...d-840e2d5044d7

The author with her family at San Francisco Pride in 2015.

But the attacks would not stop.

Anonymous trolls on Twitter, some with nearly half a million followers, said people should boycott Levi’s until I’d been fired. So did some of my old gymnastics fans. They called the company ethics hotline and sent emails.

Every day, a dossier of my tweets and all of my online interactions were sent to the CEO by the head of corporate communications. At one meeting of the executive leadership team, the CEO made an off-hand remark that I was “acting like Donald Trump.” I felt embarrassed, and turned my camera off to collect myself.

In the last month, the CEO told me that it was “untenable” for me to stay. I was offered a $1 million severance package, but I knew I’d have to sign a nondisclosure agreement about why I’d been pushed out.

The money would be very nice. But I just can’t do it. Sorry, Levi’s.

I never set out to be a contrarian. I don’t like to fight. I love Levi’s and its place in the American heritage as a purveyor of sturdy pants for hardworking, daring people who moved West and dreamed of gold buried in the dirt. The red tag on the back pocket of the jeans I handed over to the Russian girls used to be shorthand for what was good and right about this country, and when I think about my trip to Moscow, so many decades ago, I still get a little choked up.

But the corporation doesn’t believe in that now. It’s trapped trying to please the mob—and silencing any dissent within the organization. In this it is like so many other American companies: held hostage by intolerant ideologues who do not believe in genuine inclusion or diversity.

In my more than two decades at the company, I took my role as manager most seriously. I helped mentor and guide promising young employees who went on to become executives. In the end, no one stood with me. Not one person publicly said they agreed with me, or even that they didn’t agree with me, but supported my right to say what I believe anyway.

I like to think that many of my now-former colleagues know that this is wrong. I like to think that they stayed silent because they feared losing their standing at work or incurring the wrath of the mob. I hope, in time, they’ll acknowledge as much.

I’ll always wear my old 501s. But today I’m trading in my job at Levi’s. In return, I get to keep my voice.